If the world ever needed a Rachel Carson, it is now. Why do I say that? Because Rachel Carson witnessed environmental degradation in her lifetime and took action at great risk to herself, both professionally and personally.

Rachel Carson is my next Rhetorica Heroica!

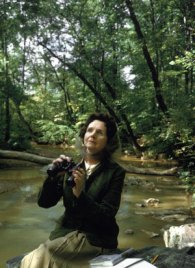

Rachel Carson (1907-1964) was an American marine biologist, ecologist, and nature writer. After 15 years working for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Carson retired to devote more time to her writing.

What twists and turns in life took this little nature-loving girl from Pennsylvania to wage one of the nation’s fiercest battles? Carson endured harsh criticisms, not only for being a whistle-blower, but for daring to engage in the male-dominated world of the scientist in the 1950s and 60s. She was trained as a scientist, yes, but what really kept her on task were the ingrained values of Courage, Determination, and the firm grasp of Certainty!

Carson wrote stories from a very young age, first to acquaint readers with the wonder of the oceans and rivers, and then as a conscientious scholar when she wrote her magnum opus, Silent Spring (1962), which shook the nation with its strong environmental message.

The use of DDT, the savior of the agricultural science business, was killing everything in its path, all life, including humans. Her awakening came when she realized the waters near her home, once alive with chirps and squawks of birds, was now silent. She searched until she found the source of such silence. What she found traced back to chemicals in the air and water. Carson’s cry was “what kills the birds will kill us” and she was right. As a scientist she knew how to back up her claims-with empirical data.

Carson’s book warned humankind of the destructive path they were on in their use of pesticides and insecticides in agriculture, like DDT. DDT, (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), according to U.S. Geological Survey, is an “insecticide highly toxic to biota, including humans…a persistent biochemical which accumulates in the food chain.” Imagine airplanes circling your neighborhood and outlying countryside spraying DDT down in a fine mist, covering everything. Soon birds are quivering, shaking uncontrollably, then falling from the sky. People are eating local foods, drinking the water, and getting sick and dying from strange cancers. Think of a myriad of respiratory illnesses plaguing young and old….all the while chemical companies denying any connection of sufferings to their products.

And what about now? Almost 50 years since Carson wrote Silent Spring, the earth is ailing, in need of aid more than ever, inhabited by threatened species, including humans. It seems incomprehensible to think we will survive at the current rate of annihilation and apathy regarding our planet that has seized the earth’s human inhabitants. We humans have certainly had our harbingers, our oracles, our soothsayers, who have heralded, and warned us…and these warnings only cause a pause in the march of “progress.” Where is our Rachel Carson? Muzzled by government, lobbyists and big money?

Rachel Carson was one who tried to halt the destruction against all odds, in the face of ridicule and opposition. She risked humiliation from the highest levels of national government. She dared to play hard ball with the Big Boys, and she won. The chemical companies retreated after her ally, President John F. Kennedy, took notice, read Silent Spring, and launched a full-scale congressional investigation. Soon Carson was called to testify against the chemical companies. All told, “the President’s Science Advisory Committee issued a report in 1963 largely backing Carson’s scientific claims. By 1970, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was established as a cabinet-level position and, in 1972, DDT use was banned…the publication of [Silent Spring] is credited as one of the most influential events in sparking the environmental movement” (see fws.gov below).

Below is an excerpt from Silent Spring, Chapter 12, “The Human Price”:

As the tide of chemicals born of the Industrial Age has arisen to engulf our environment, a drastic change has come about in nature of the most serious public health problems. Only yesterday mankind lived in fear of the scourges of smallpox, cholera, and plague that once swept nations before them. Now our major concern is no longer with the disease organisms that once were omnipresent…Today we are concerned with a different kind of hazard that lurks in our environment–a hazard we ourselves have introduced into our world as our modern way of life has evolved. (187)

In tragic irony, while Rachel Carson was battling for the environment’s health, her own health was in decline as she fought the losing battle with cancer (no implication of DDT poisoning), succumbing in 1964, less than a year after the congressional hearings. Rachel Carson, true Rhetorica Heroica, in the face of her own mortality, fought for change through her writings.

For more detailed information on this courageous woman rhetor, please access the following links:

Rachel Carson: rachelcarson.org

Information on DDT: http://toxics.usgs.gov/definitions/ddt.html

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: http://www.fws.gov/northeast/rachelcarson/carsonbio.html